This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

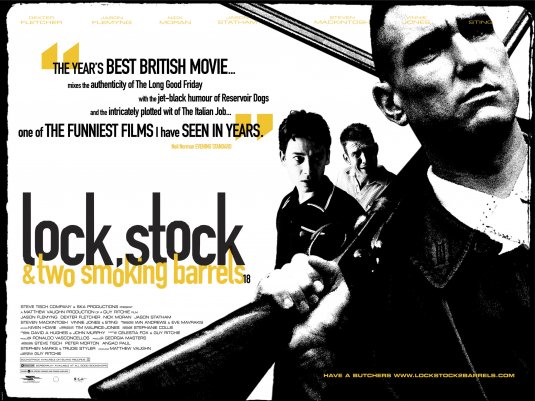

Their early collaboration is much like that of the scheming gangsters who occupied the majority of Guy Ritchie and Matthew Vaughn’s breakthrough films. Two young English gents who set up London based production company, Ska, off the back of a script written by Ritchie, titled Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels. Both with big ideas and even bigger dreams; Vaughn was the business minded money man, while Ritchie was the creative firebrand.

It took them a couple of years to get the financial backing to begin filming, but once they did, it was the start of a process that would lead to one of Britain’s most seminal films, kickstarting an entire London gangster sub-genre, and triggering two very different career trajectories.

Lock, Stock was released on the 28th August 1998, and went on to gross over £11m at the UK box-office. It subverted the hip coolness of Tarantino, applying a grimy, sticky table top veneer to that filmmaker’s signature crime canvas, which was all the rage at the time.

Whilst there were undeniable nods to his Pulp Fiction counterpart, Lock, Stock also shaped the unique visual template that Ritchie would carry with him, even into the realm of King Arthur. The freeze-frames at narrative junctures, the frantic editing interspersed with flashy slow-mo, the colour pigments and drained palettes. Some might say that this geezer is a one-trick-pony.

Well that trick worked to the tune of over £50m at the global box office with follow-up, Snatch. With Vaughn on producer duties once again, and with their burgeoning reputations, it afforded them a larger budget (£5m) and some real star clout in the form of Brad Pitt’s memorable turn as Mickey O’Neill.

Given the time and money to fully realise his vision, Ritchie was able to shape this rough diamond (the original title of the film), into arguably his most cohesive movie. Marrying a script as sharp as the dialogue, with a visual flair that manifested in those boxing sequences, or timelapse montage editing before we’d even heard of Edgar Wright, Snatch was to be the collaborative high point for the two. Inevitably, from such a high there would be room for a fall, but how far that would be and how wide their division would become, was unimaginable.

Ritchie’s next three pieces of creative output would be in tandem with his much publicised relationship with Madonna. There was a music video for What it Feels Like for a Girl, a short film called Star, and then a movie with a cultural impact as large as Lock, Stock, but for the opposite reasons. It wasn’t so much Lock, Stock as laughing stock, when Swept Away was released in 2002, and it did just that, to Ritchie’s reputation, and to his partnership with Vaughn.

It would be the last time the two would work together, and after the BBC said “This waterlogged romantic comedy really does deserve to sink without a trace” and the New York Post claimed it as “butt numbingly BORING”, you can’t really blame them. For the record, it’s not an abomination, it’s just not very good.

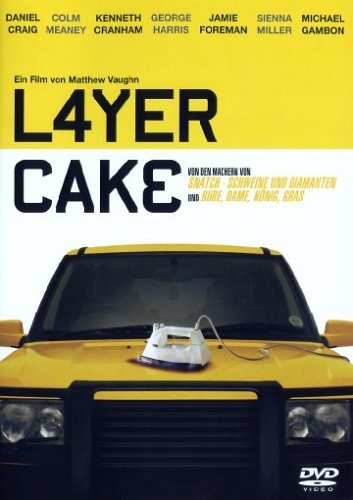

What this did was create Matthew Vaughn, the director, and he stuck to what he knew best by helming Layer Cake in 2004. A more polished take on the criminal world than the boozer and back alley ones he’d operated in with Ritchie. His film was less showy, but ultimately more cinematic. The Duran Duran cafe confrontation, Sienna Miller’s dancefloor sequence, or the Michael Gambon Facts of Life monologue; all are memorable in a way that’s the antithesis of what his former partner created.

Speaking of Ritchie, he was making something parallel to Layer Cake, his own take on organised crime starring his go-to-guy, Jason Statham, in the hope that he could tap into that bottled lightning of his first two films. It was Revolver. A convoluted, nonsensical, self-indulgent exercise in trying to be deep, that just comes off as pretentious. It would be three years later, with 2008’s RocknRolla, that his career trajectory would show the first signs of an uptick, and in a move indicative of both Vaughn and Ritchie’s career synchronicity, the two would head to Hollywood.

Initially things looked bright for Vaughn as he landed the X-Men: The Last Stand gig, but these were different times for superhero movies, when meeting a release date was more important than making a good movie, and he eventually jumped ship, allowing Brett Ratner to take the helm and make a film the makes X-Men: Apocalypse seem like Apocalypse Now.

Vaughn would dust himself off and try to invoke The Princess Bride with the truly wonderful, Stardust. Unfortunately it would suffer that films fate, and stiff at the box-office, only to be cherished as one of those films that you can’t turn off should you stumble across it whilst channel surfing. It was a film that showcased Vaughn’s ability to handle a different genre, infusing the fantasy adventure with a big beating heart, and it was his first teaming with writing partner Jane Goldman, who would go on to become something of a secret weapon for the director.

The end of the noughties would be pivotal for both; Ritchie would throw himself headfirst into the studio system by directing the Robert Downey Jnr and Jude Law blockbuster, Sherlock Holmes. It featured his usual colour filter, a unique way to integrate his slow-mo montages into Sherlock’s deductive sequences, and a smattering of decent humour. It was pure Ritchie, filtered through a recognisable brand, and it made over $500m worldwide. Now he was a bankable go-to Guy.

Vaughn on the other hand had been burned by the X-Men debacle, coupled with the lukewarm reception given to Stardust, so tapped into the same business nous which had helped set up Ska Productions all those years ago, to put his hand in his own pocket to self- finance an ultra-violent adaptation of a Mark Millar comic book that Hollywood wouldn’t touch with a barge pole. He was about to Kick-Ass.

The story of Dave Lizewski (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), a young superhero taking on the establishment, was perfectly attuned to what the director was doing himself. Kick-Ass was one of the best films of 2010, a refreshing antidote to the sanitised world of The Last Stand he’d been forced to abandon. It’s no coincidence that by the time Hollywood cottoned on to the fact that Vaughn was a talent, he’d jumped ship and the sequel turned out to be offensively risible.

2011 saw the two friends release blockbuster sequels; Ritchie’s was the follow-up to his own film, with Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows, which matched the box-office take of its predecessor, but was largely paint-by numbers. Vaughn was given the chance to resurrect the X-Men franchise, taking megaphone duties on First Class, and delivering a triumphant return for a series that had been treated shoddily from the Studio downwards.

Perhaps fearing that the success of First Class might bring about a similar level of pressure that forced him to walk from The Last Stand, Vaughn decided to abandon the mutants after one film, and set about returning to adapting another little-known Mark Millar graphic novel, Kingsman: The Secret Service.

At about the same time, in another coincidental moment of career alignment, Guy Ritchie was prepping his own spy caper, with an updating of 70’s television show, The Man from U.N.C.L.E. Despite being an undeniably fun knockabout romp, it tanked at the box-office, probably too genteel for an audience expecting explosions, or at the least, some Ritchie tropes. It was probably his most mature film, in terms of aesthetics and target audience. It’s a shame that it underperformed, because his latest, the oft-delayed King Arthur: Legend of the Sword, appears to be smothered in the visual ticks we’ve seen countless times before.

In the same summer of 2017 that King Arthur is being released, Vaughn will unleash his sequel to Kingsman, a film that was embraced both critically and commercially, becoming his most profitable film to date. The Golden Circle is one of the most eagerly anticipated films of the blockbuster season, opposed to the trepidation with which King Arthur is being met. It’s a topsy-turvy pattern symptomatic of the duos rise from the East End of London.

Both have had smoking barrels, both have had damp squibs, and who knows, sometime in the future, this couple of geezers might just get the gang back together.

Image: Screen Gems/20th Century Fox